Tenacious and gentlemanly, even when brought low by chronic coronary artery disease, my metalworker father was going to die. Or at least that’s what 11-year-old me thought. A number of heart attacks and ongoing angina had rendered dad unfit to continue the life of heat, flames and particulate-heavy fumes, and prolonged exposure to ultraviolet light, that he’d known during the course of his decades as an A-grade welder and boiler maker. Soon enough I was bedside in the intensive care unit of the Queen Elizabeth II Jubilee Hospital, not far from our modest weatherboard home in Salisbury East, listening to talk of coronary artery bypass surgery and praying that, whatever the procedure constituted, it would somehow free dad of his wretched state and restore him to his reassuringly stoic best.

Tenacious and gentlemanly, even when brought low by chronic coronary artery disease, my metalworker father was going to die. Or at least that’s what 11-year-old me thought. A number of heart attacks and ongoing angina had rendered dad unfit to continue the life of heat, flames and particulate-heavy fumes, and prolonged exposure to ultraviolet light, that he’d known during the course of his decades as an A-grade welder and boiler maker. Soon enough I was bedside in the intensive care unit of the Queen Elizabeth II Jubilee Hospital, not far from our modest weatherboard home in Salisbury East, listening to talk of coronary artery bypass surgery and praying that, whatever the procedure constituted, it would somehow free dad of his wretched state and restore him to his reassuringly stoic best.

We didn’t enjoy much in the way of financial or social resources, but mum did her best to keep our small family functioning, taking on additional dressmaking work (which she undertook from home) at an already stressful time. Morale was low, the mood anguished and uncertain, and – despite my having been recently introduced to the wonders of Iron Maiden and their triumphant fifth album, Powerslave – the house perpetually quiet and chilly. That year, the weather in Brisbane had been punctuated by terrifically powerful thunderstorms and plenty of rain. The passing days and weeks came to resemble one long, cold, rainy, dread-filled afternoon. I felt very alone and often was. In such black times, it seemed to me that the best way out was in.

My best friend then and now, Michael Taylor, had introduced me to Fighting Fantasy gamebooks the year before, initially via Steve Jackson’s The Citadel of Chaos and, soon after, the slipcased Sorcery! two-book set containing The Spell Book and The Shamutanti Hills. Russ Nicholson’s darkly twisted and subtly decadent line work, paired with John Blanche’s outlandish proto-punk-metal grotesqueries, pretty much defined the Fighting Fantasy continents of Allansia and the Old World for me (although Malcolm Barter, Iain McCaig and Alan Langford each brought their own idiosyncratic charms to the visual rendering of Ian Livingstone and Steve Jackson’s fantastic lands). The appearance of Warlock: The Fighting Fantasy Magazine at our local newsagency later in 1984 saw my immersion into gamebooks complete.

My older brother and his high school mates ensured that, between 1984 and 1985, my musical world expanded from Billy Idol’s Rebel Yell and Synchronicity by The Police to encompass heavy metal: Judas Priest, Accept, Saxon, Dio, Motörhead, Def Leppard, Scorpions, Y&T, Yngwie J. Malmsteen, Ozzy Osbourne, and almost incomprehensible amounts of Iron Maiden. Then highly controversial, and with its outlandishly poetic and frequently fantasy-inspired lyrics elaborating upon themes of warfare and witchcraft, religion and rebellion, madness and mythology, heavy metal provided the perfect musical accompaniment to my premier existential crisis.

The outrageously subversive British sci-fi anthology comic 2000 AD provided further grist to the mill of my bewildered juvenile attempts to resolve the crisis of existence. With its cast of murderous anti-heroes and warped misfits – ranging from the brutal fascist lawman of the dystopian future (Judge Dredd) and a ‘deviant’ alien warlock (Nemesis the Warlock) to gun-slinging mutant bounty hunters (Strontium Dog) and the 50th century ‘everygirl’ who went out and did everything (The Ballad of Halo Jones) – each weekly ‘prog’ of “the galaxy’s greatest comic” was a veritable powder keg of violent degeneracy, dark political and social satire, and rampant anti-authoritarianism. 2000 AD provided a predominantly futuristic foil to the honourable and courageous adventure of Fighting Fantasy that, in my naiveté, I found so compelling.

By the time dad was being prepped for heart bypass surgery – to have the great saphenous vein removed from one of his legs and one end attached to his aorta and the other end to the obstructed artery (after the obstruction, restoring proper blood circulation) – I was in Grade 6A at Salisbury State Primary School. Our teacher, Mr. Cunningham, was an articulate and accommodating mentor who recognised the profound creative potentials embodied by gamebooks and comics, especially in terms of cultivating readings amongst boys. He encouraged me and Mike and a few other lads to start and run our own library at the back of the classroom.

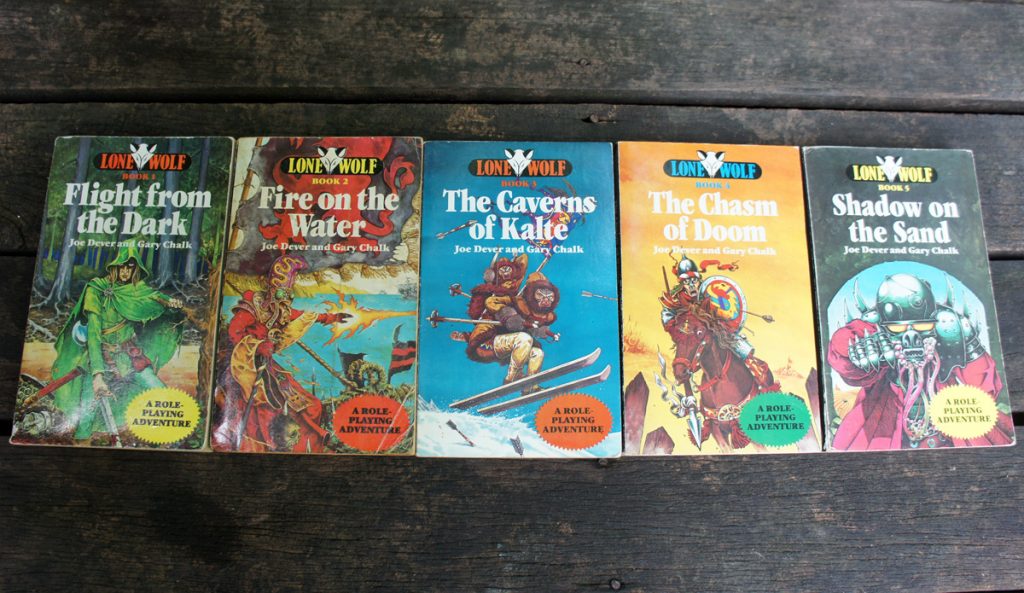

Predictably enough, the core of our library collection consisted of weekly progs of 2000 AD plus the monthly Eagle Comics’ editions of Judge Dredd and the first volume of The Judge Dredd Collection (collecting the strips that appeared in The Daily Star newspaper for many years, illustrated by Ron Smith). Towards year’s end The Best of 2000 AD Monthly would also be available. Gamebooks-wise, we pooled together our Fighting Fantasy books and copies of Warlock magazine alongside outliers like J.H. Brennan’s GrailQuest, the Time Machine interactive novels, the Be An Interplanetary Spy series of comic-style illustrated gamebooks, the Find Your Fate: Indiana Jones gamebooks, and some of the less lame Choose Your Own Adventure books – and Joe Dever and Gary Chalk’s unexpectedly brilliant series, Lone Wolf.

With an ongoing narrative centered upon Silent Wolf’s sudden and traumatic immersion into a world of loss and severe uncertainty, Lone Wolf precisely embodied all that occupied my inner world: devastation, powerlessness and despair; fighting on despite the fear and growing more resilient in the proximity of death, and undertaking an internal dialogue – terrifying yet necessary – with the shades of an emergent existential realisation. By the time dad’s sternum had been sawn open and wired closed again, as part of his triple bypass, as Lone Wolf I’d survived the massacre of the Kai by the Darklords (Flight from the Dark), battled the death-hulk fleet of Vonotar the Traitor off the Kirlundin Isles (Fire on the Water), and – Sommerswerd in hand – further pursued the much-loathed wizard across the icy Kaltersee to the barbaric northern wastes of Kalte (The Caverns of Kalte).

The interconnected narrative of the Lone Wolf gamebooks reinforced what had already become apparent to me, sitting by dad’s hospital bed: death mattered – it limited, liberated and, ultimately, defined. My beloved father, trials and afflictions he was destined to endure. As a child, I did all that I could to comfort him: talking when he seemed to want to talk, quietly reading or drawing when he seemed caught up in his own turmoils, or simply waiting nearby – with mum and my books and felt-tip pens and scrounged old squares of ‘drawing paper’ – when the nurses drew the curtains in order to amend his bodily indignities. During those days and weeks of 1985, a kind of simplicity descended upon me: Lone Wolf must prevail! Dad must not die! The Darklords must be defeated! The slumbers of the grave must wait, some more years yet …

Twenty-one years would pass before I’d watch my father’s coffin being lowered into the Mt. Gravatt dirt; an almost-disturbingly clear mid-morning, late autumn. Another 11 years on, and acutely aware that time is a gift not to be squandered, Magnamund beckons once more.

(header Illustration courtesy of Rich Sampson/artofnerdgore)

Wow. What a story, I’m glad that there was so much good to get you such a tough time. You’re very fortunate to have been blessed with so much more time with your father.

My own memories of Lone Wolf are a period of loneliness and isolation when we moved from Sydney to Melbourne. Money was tight and an extroverted kid turned introvert found an amazing escape in the pages and stories of Magnamund.

I think it’s time for that kid to rediscover Lone Wolf.

Bloody hell. Sheer poetry, that.

A beautifully written piece. The hobby has gotten me through some rough times too – I’m glad you could find your escape.