As a setting, cyberpunk is unequivocally a product of its time. Defined by its polarised classes and advanced technology, it could be considered as the rising sentiments of the 1980s taken to their extremes. While parallels and comments on society have to be purposefully added into other genres and other kinds of ‘higher’ science fiction (I’m thinking Iain M. Banks’ Culture novels, or Dune), cyberpunk’s social critiques define its very nature. Without that aspect of a yawning societal divide, it’s just science fiction. The word punk is there for a reason.

In order to have a low-life protagonist get hold of some high-tech gear, the tech needs to have come from somewhere with a lot of funding. In order to have the neon advertisements that glare down at pedestrians on the street corner, there needs to be a corporation buying the advertising space. It comes as no surprise that this subgenre of mega-corporations and widespread poverty emerged during the Reagan/Thatcher era. This is a capitalistic setting more than most, something that distinguishes it from its sibling genres in the way it is consumed as well as portrayed. It’s doubtful that the CEO of a multinational could enjoy something like Shadowrun in the same way that you or I would (although who knows). Anyone can picture themselves as Ripley, or Paul Atreides, or Michael Burnham, but with cyberpunk the class system is fixed firmly in place, and provides a more personal brand of escapism. Because you connect with the characters on the bottom rungs of a society modelled on our own, it’s easier to invest in them, and exciting if they get to stick it to the man upstairs or a chance of escaping their poor lives. In this context something like Elysium could be considered cyberpunk, although it is perhaps a bit too sunny.

Nostalgia plays a big factor, as with other products of the 1980’s that seem to endure endlessly. Not many subgenres have a sense of nostalgia attached to them. Polluted megacities may appear depressing, but the environment carries with it a sense of hope, or at least of looking to the future. The societies depicted by William Gibson, Philip K. Dick and others may be rotting, decayed things, but their presence within sprawling cities implies progress, and while life may not be pleasant, there is at least that recognisable sense of moving forward. This hope was lost with the later prominence of post-apocalyptic fiction, reflecting more recent sentiments of things being too late, already disastrous, rather than the lingering optimism of the 1980’s. This helps to explain the noir, or detective story elements commonly twinned with cyberpunk. Classics like Blade Runner and Neuromancer contain those strong noir elements that infer at a bigger picture, an unfolding mystery and a sense of the unknown. You won’t see many detective stories set in a post-apocalyptic world (the closest thing that comes to mind is The Rover, although even that is without mystery, just a man following leads). After a global disaster, people are usually just trying to survive. Meanwhile utopian science fiction, things like Brave New World, or speculative fiction like The Three-Body Problem can also contain elements of mystery much easier because the world is in a period of relative stability or growth, able to hint at things yet to be discovered.

In this way, the opportunities within cyberpunk worlds are enhanced by futurism, but not constrained by it. While a post-apocalypse setting puts a full stop on the advance of technology, and with it our sense of progress, cyberpunk allows us to connect with the parts of everyday life we are familiar with while keeping our imaginations open to ways for things to change. Having so many parallels with reality, a cyberpunk world works as much on implication as description, and at the creator’s discretion, can thrive off the most mundane object or activity (these ideas are explored further in Lawrence Person’s Notes Towards a Postcyberpunk Manifesto). The image of chem-addicts huddled in an alley implies the presence of dealers and producers, and associated crime, and so maybe some police patrols but clearly not enough to tackle it all, and before I know it I’m thinking about how this city funds its police department. We are allowed to make those jumps by ourselves because of the limitations of the setting, but it’s still spacious enough to fire the imagination like only science fiction can.

There is a great example of this in Blade Runner 2049, when Mariette says to K simply, “I’ve never seen a tree”. By itself the line is dystopian but the viewer has been pulled into this world by the enormous Atari and Coca-Cola adverts, and begins to consider what things would actually be like without trees, a classic sort of dark twist on reality, and the imagination is then left to itself. The social divide is later highlighted when we see that the office of Niander Wallace, super-rich industrialist, is furnished with wood. Maybe the point I am making is that there is a great deal of scope that can be expressed in such a short burst of flavour, and a reader, viewer or player’s imagination is given the room and the fuel to stretch out.

There is a great example of this in Blade Runner 2049, when Mariette says to K simply, “I’ve never seen a tree”. By itself the line is dystopian but the viewer has been pulled into this world by the enormous Atari and Coca-Cola adverts, and begins to consider what things would actually be like without trees, a classic sort of dark twist on reality, and the imagination is then left to itself. The social divide is later highlighted when we see that the office of Niander Wallace, super-rich industrialist, is furnished with wood. Maybe the point I am making is that there is a great deal of scope that can be expressed in such a short burst of flavour, and a reader, viewer or player’s imagination is given the room and the fuel to stretch out.

For an example of broader context, compare cyberpunk with a fantasy setting. Without being specific, the day to day existence of a typical fantasy world inhabitant would likely require much more definition in order to begin establishing the rules of the world. The reader will begin a fantasy tale with a thousand different examples in their heads, and to an extent it is up to the particular world to malleate the reader’s preconceptions, collected from past experiences, to create the immersion. Cyberpunk negates this problem because it is directly relatable. Fantasy worlds are separate from our own, based on time periods we have only read about, and so we tend to rely more on previous examples. In some ways, the setting is broader but the imagination is more confined.

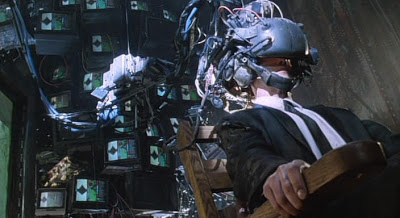

Any examination of cyberpunk would be inadequate if it did not mention style. Cyberpunk has style at its core. Data constructs flicker with unnatural light, corporate grids shine chrome, shadowy programs lurk in neural networks and behind restricted terminals. Fibreoptic bundles snake across bare floorboards. Hackers, jacked up on synthetic drugs, hunch over their consoles with bandaged hands and splinted wrists. Outside in the fog, a police drone hovers past the window, silhouetted against a glowing advertisement for some innocent product. Dark, immoral, and often violent, these worlds are appealing because of their presentation as much as anything else. The descriptions, cinematography, costume design, everything needs to lean in the same direction. Sometimes it’s as simple as saying; this is cool as fuck. These worlds can unveil grand, sweeping themes and provide commentary on modern societies, but the real appeal lies in it being done with style. Deus Ex explores transhumanism, how cybernetic implantations could impact society and culture, but the protagonist has got to wear sunglasses and a trench coat. James Cameron’s middling Strange Days takes a look (more of a passing glance, really) at police brutality and racial tension in 90’s Los Angeles, and stands out through its ‘playback’ scenes of characters’ memories shot from a first-person perspective, a conscious stylistic choice and a big logistical effort for a film made in 1995. William Gibson’s Johnny Mnemonic, a story with Yakuza assassins and a cybernetic dolphin, introduced the idea of a merciless, tech-induced plague sweeping the populace, and of course we can draw parallels with AIDs in 1980’s America.

Any examination of cyberpunk would be inadequate if it did not mention style. Cyberpunk has style at its core. Data constructs flicker with unnatural light, corporate grids shine chrome, shadowy programs lurk in neural networks and behind restricted terminals. Fibreoptic bundles snake across bare floorboards. Hackers, jacked up on synthetic drugs, hunch over their consoles with bandaged hands and splinted wrists. Outside in the fog, a police drone hovers past the window, silhouetted against a glowing advertisement for some innocent product. Dark, immoral, and often violent, these worlds are appealing because of their presentation as much as anything else. The descriptions, cinematography, costume design, everything needs to lean in the same direction. Sometimes it’s as simple as saying; this is cool as fuck. These worlds can unveil grand, sweeping themes and provide commentary on modern societies, but the real appeal lies in it being done with style. Deus Ex explores transhumanism, how cybernetic implantations could impact society and culture, but the protagonist has got to wear sunglasses and a trench coat. James Cameron’s middling Strange Days takes a look (more of a passing glance, really) at police brutality and racial tension in 90’s Los Angeles, and stands out through its ‘playback’ scenes of characters’ memories shot from a first-person perspective, a conscious stylistic choice and a big logistical effort for a film made in 1995. William Gibson’s Johnny Mnemonic, a story with Yakuza assassins and a cybernetic dolphin, introduced the idea of a merciless, tech-induced plague sweeping the populace, and of course we can draw parallels with AIDs in 1980’s America.

Cyberpunk can be escapism, mystery, or a veil to drape over our own culture in shadowy folds of neon and rain. Any facet of it can be dialled up, emphasised or avoided and it will retain that foundation that makes it such an iconic genre. Building upwards from that, making a story worth telling, characters worth caring about, a sprawling cityscape worth immersing in, is the creator’s job.

Wonderful article, thoroughly enjoyed it. PLUS Fear Factory at the end – 10/10.

About this – “You won’t see many detective stories set in a post-apocalyptic world” – would Fallout 4 count as this, do you think? I know its not the overall thrust of the plot, but does make up a fair chunk of it.

Glad you liked the article Newt and thanks for reading! I tend to forget Fallout 4 exists because I found it so utterly disappointing on every level, however you are right. The detective bits felt a little bit shoe-horned in, but they were there. Compared to something like Neuromancer, where Case uncovers a sprawling global conspiracy, the detective elements of Fallout 4 (and 3, if I recall) were much more about following leads through environments without things ever expanding in scale. am I wrong? was the Enclave so bland i’ve forgotten all about it? There is a difference to me, but perhaps a subjective one. It’s been a while since I played it…